by Kitty Costello

Dean Lipton: A Portrait

Crossing Civic Plaza

every Tuesday evening—

a figure tall with hooked coat,

his gait pivotal,

a book bag slung shoulder high

accenting the triangular outline,

the bag clinking faintly;

within, the books and papers and empty tuna cans.

His voice, in parallel discongruity,

rumbling kindness through his layers of awesome monumentality.

He was a walking cave

glimmering sound.—Elinor Randall (aka Randy)

Every Tuesday evening, just before 7 p.m., Dean Lipton would lumber into the first floor Lurie Room in the old Main Library with his City Lights shoulder bag filled with a clatter of old tuna fish cans, which he would pass out as ashtrays to all the smokers. (Yes, you could smoke in the library in those days.) Just inside the front door, each of us would be greeted by kindly old Rusty Evans, a playwright—always wearing his signature canvas fishing hat—ever-present with his yellow legal pad, collecting names and addresses of every writer who walked in. This tradition began because Dean had seen more than one cherished writer suddenly disappear, with no way to find out if they were okay or what became of them or their work, and he didn’t want that to ever happen again.

Dean would sit at a table up front as if on stage, with a reader’s chair pulled up beside him, while we, the “audience,” sat in straight rows arranged like theatre seats. This is in contrast to later moderators’ preference for having a circle of chairs. Dean would call us up one by one to sit next to him and read our work. Sometimes he would look over the pages as the reader set them aside. (There were no shared copies back in the days of typewriters, so he was the only one who got a look at the printed words. Everyone else just listened.) Always he would have one of his Pall Mall straights burning. He was often seen with his elbow resting on the table, his chin propped on his upturned palm, his cigarette dangling between his fingers, the smoke curling up beside his head, a rapt attention on his face, the ash on his cigarette growing longer and longer and longer, until he would finally go to flick it, and the ash would invariably fall off on the table before he made it to the tuna can ashtray. After the reader finished, he’d ask in his big, gruff, cave of a voice, “Okay, what are the comments?” and a lively discussion would ensue.

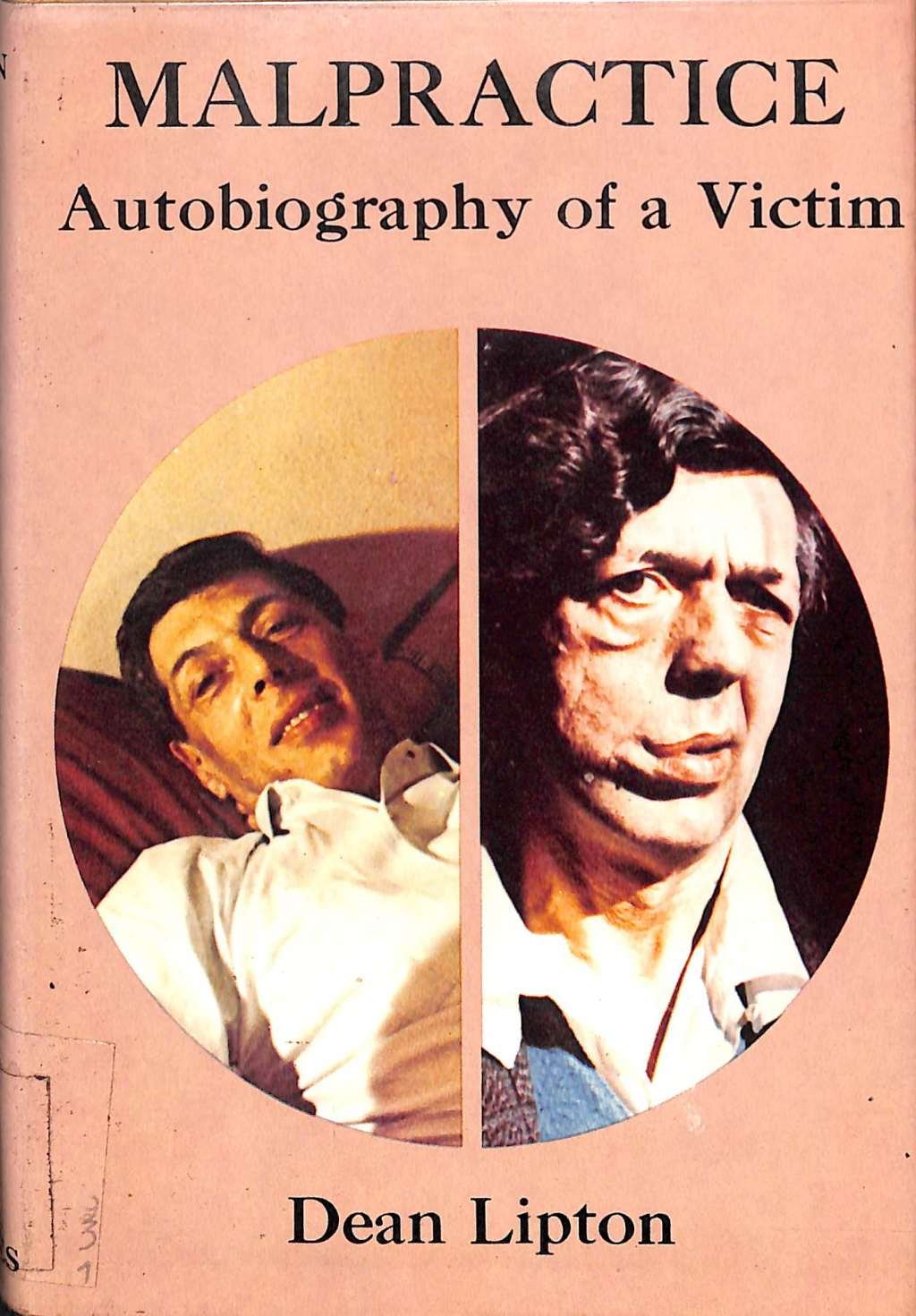

No one can properly envision the Workshop during Dean’s reign without recalling Dean’s astonishing appearance. He was a towering hulk of a man with a terrible sagging wound on the whole right side of his face. Once handsome, he had been mutilated by the slip of a surgeon’s knife, which severed a facial nerve, leaving his eye, his cheek and the right side of his mouth paralyzed. His lower eyelid hung down and teared constantly. His sagging cheek puffed out with air as he spoke, making his speech often difficult to understand, and this was after several corrective surgeries. As writer Daniel Borgstrom so bluntly put it: “Dean looked like a wax figure that was left too close to an open flame.”

In addition to his appearance, Dean was known for his growling, blunt and dictatorial manner, which kept in check the boisterous ego of many an opinionated writer. Yet he could be most kind and candidly supportive, bursting forth with a shower of praise for writers whose work showed promise. He had an almost boyish enthusiasm, and more than one generation of writers gratefully benefitted from his irascible guidance. In his own writing, Dean championed underdog causes, a spirit that came in no small part from being a (very secular) Jew who had lived through the Second World War.

Some complained that Dean had no manners, but it was more like he was unaware that manners existed. Truth-seeking mattered more than any of that. He followed his own whims, letting certain comments be made while cutting others short in an often-autocratic way. Yet there was a method to his growls and barks. For one thing, he had no tolerance for pretentiousness, literary or otherwise, and he would quickly put a stop to any bombast. If he was excited about a writer’s work, he might exclaim something like, “You could be the next Jack London!” Or he could be painfully honest if he felt the need, barking things like, “Your characters are flat. If you don’t learn to make them real, you’ll never be a writer.” He also used his gruffness to protect writers from abusive comments, rudely yelling things like, “Shuddup! You don’t know what you’re talking about,” to stop others from being rude. He understood the devastating impact overly-harsh criticism could have and admonished us to use care because, “That writer might go home and not write another word for six months!” I had the feeling he was speaking from experience, both as the critic and the critiqued.

Dean’s greatest passion was understanding the creative mind and human genius at work. (In 1970, he published a book called Faces of Crime and Genius, telling the remarkable stories of several nefarious geniuses from history.) He fervently believed in each writer’s own creative spark, encouraging each unique, individual voice. He detested formulaic writing. “Writers should grow like weeds,” he would say, and he cut short comments that seemed to him like too much “pruning.” He would likely not be happy to see today’s ubiquity of MFA programs and graduates.

Back then the group was peppered with lots of Depression-era leftists, Beat and hippie poets, and union organizer types, who gave the Workshop an anti-establishment, fight-for-the-little-guy undercurrent, very much in line with Dean’s own sentiments. On the whole, we could be a scruffy lot, Dean included.

A doctor named Phil (no, not that Dr. Phil) touched into those underdog sentiments when he read his travelogues that depicted ritzy, lavish globe-trotting. A wave of objections arose from those who disapproved of the way Phil reveled in his opulent lifestyle. Dean cut their protests short, reminding us, “We’re here to discuss what the man wrote, not how he lives. If I were to travel, I’d sleep under a bridge,” said Dean, “but that’s beside the point.” Later Phil read a draft of an article lamenting the plight of physicians who were being sued for malpractice by greedy scam artists. Who knows how Dean, who had sued his own doctor for malpractice, felt about that. He gave only his usual detailed, technical critique of the author’s craft. With so many ragtag writers attending the group back then, you could tell that Dean relished the prestige and validation of having a doctor-writer in our midst, so he gave Phil plenty of latitude.

Dean was a stickler for factual and historic accuracy, both in his own writing and in the writing of others. He would tolerate long discussions if it was a matter of getting the facts straight. He especially relished the chance to parade his own considerable knowledge when a writer touched upon a subject he had studied deeply, especially if the subject was Native Americans, the nature of genius, the American frontier, or the literary history of San Francisco. In his own writing, he liked to weave factual tales with many intricate twists and turns revealed one by one, point by point, highlighting the range of opinions on the subject, then revealing his own finely-wrought conclusion.

He was most comfortable commenting on prose, and non-fiction was his forté. He would facilitate the group’s response to poetry but would comment on poems only sparingly. “Poetry is hard to criticize,” he would say, giving a wide berth for the inner process of the individual poet. One young regular, Andrew Wells, who attended in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, read poems full of incomprehensible yet compelling images. For example:

Sight owed to the windows, even blue;

machines look askance from the

Conquistadors of Beef

who look askance at each other…

One night after the group had engaged in a lengthy discussion of the possible meaning of one of Andy’s poems, Dean burst forth, “Andy, you’re either a total genius or you’re full of bull. We can’t understand it well enough to tell.”

Dean’s own creative process was seriously derailed by his ill-fated surgery, and he could barely write for years afterward. In his 1978 book, Malpractice: Autobiography of a Victim, Dean describes the Writers Workshop as his lifeline, keeping him in touch with people, with writing, and with the creative process. When so many aspects of his life had been turned upside down, Dean’s role as moderator gave him an ongoing stature and sense of dignity, which might otherwise have been lost. Workshop-veteran Leonard Irving described Dean as “a frustrated swashbuckler who wanted to be a war hero or Jim Bowie or a desperado, saddled and bridled and riding into the sunset, but he never got within five feet of a horse, and his dashing looks were robbed from him so suddenly.”

Dean stayed up late every night, most often hanging out in North Beach cafes and bars, wrangling with the likes of Kirby Doyle, Howard Hart, Tisa Walden, Neeli Cherkovski and Jack Hirschman. His sleep was nightmarish, he told me, flashing him back again and again to the trauma of his surgery and its aftermath. So he tired himself out by wandering the nighttime streets until the wee hours, finally making his way back to his Cabrillo Street apartment, often just before dawn. If he gave you his phone number, he was sure to say, “Don’t call before 1:00!”

Before life dealt him that fateful blow, Dean Lipton had always been a man who threw himself up against the world, who came out punching before the debate had even begun. Born to a Jewish family in Detroit in 1917, he left home at age fourteen during the Great Depression, traveling the country in boxcars, working menial jobs, living in hobo jungles and migrant camps, then working for various newspapers. He moved to San Francisco in the 1930s and got involved in various leftist groups. Over time he put himself through college, was publicist for various political campaigns, was editor of a Jewish newspaper for a few years, and published numerous articles and books, including a novel. He was also a proud father and grandfather.

Dean was an original thinker who fought for what he believed in. His own writing championed causes about which he felt passionately, and his quest for justice was never roped in by current political fashion. Most notably, his writings on the case of Toguri D’Aquino, the so-called Tokyo Rose, were the first to point out the injustice done to her, and helped eventually to win a pardon for her from President Gerald Ford in the 1970s. Dean wasn’t graceful about agreements and disagreements, but he was exceedingly straightforward in a way that made him someone you knew you could trust.

Though many were understandably ruffled by Dean’s manner, Workshop writers on the whole had an unspoken tenderness for crusty old Dean. Here he was, a giant of a man with an unmistakably scarred face he couldn’t hide, staying in the public eye, holding his head up high, and even commanding respect. His awkward dignity announced that it’s possible to carry on no matter what, an inspiration to others who themselves might have felt damaged or different and felt more of a sense of ease and belonging in the Workshop because of Dean’s lumbering composure under such obvious hardship.

By the late-1980s, more and more people were living on the streets around the library in the Civic Center and the nearby Tenderloin. The Writers Workshop had always had its share of self-professed misfits, but now it began attracting more marginal folks. This included some very talented homeless poets, who always had to worry about their manuscripts being thrown in a dumpster when they were rousted out of wherever they were sleeping. It was no surprise to see Dean being sympathetic and protective of these writers.

When steep budget cuts hit the library in 1988 and the library’s evening hours were cut, there was steep competition for meeting room space, so after more than forty years, the Writers Workshop was summarily given the heave-ho and became homeless. By then I had been working for nine years at the Main Library myself. Knowing the administrators and hearing scuttlebutt from the security guards, I could see that management was relieved to have a legitimate excuse to boot the Workshop out. Dean and the group had gotten too funky for them.

Rescued by State Senator Milton Marks, the Workshop was soon given space in the nearby State Building for several years. Now to attend the group, you had to go through a security checkpoint to get to a small, florescent-lit, windowless conference room, which was not exactly inviting but was considerably better than having no meeting space at all. Without the gravitas of being housed at the library, there were no curious drop-ins. Since the Workshop had never advertised itself, word-of-mouth became the only way to attract new writers, and the group became more insular.

On top of all that, Dean was in his seventies by then, and his stamina was waning. It was not uncommon for him to doze off while someone was reading and to be heard softly snoring. Then he would wake up with a start, embarrassing everyone but himself, and carry on as if he had been paying attention all along. That was in the last few years before he died. Scottish poet and storyteller Leonard Irving was always there as backup whenever needed, and then stepped in to lead the group when Dean died in 1992.

Dean’s funeral gathering was as unlikely and unique as he was. It was held at a surprisingly-posh funeral home on Sutter Street, not far from the library. Writers who had attended through various decades of the Workshop showed up en masse to honor him, gathering around the coffin to see his blessedly-relaxed face, his always-unruly hair pasted down in a way he never would have worn it. Then we were ushered in for the service.

Dean may rank as the most unreligious person I have ever known, a man who was deeply suspicious of “true believers” of all stripes. His two daughters, on the other hand, were Mormons, in from Salt Lake. They had invited a local Mormon minister to lead the service, along with a small choir composed of cherubic-looking young men who had just returned from various missionary stints. Then there was our group of funky, unkempt North Beach and Tenderloin poet types interspersed with clean-cut Mormons and suited morticians.

Thankfully, the Mormon minister grasped the irony of the situation—that here he was, leading a Christian service for a Jewish guy who didn’t believe there’s a god, and doing it in front of a bunch of irreverent San Francisco literati. To his credit, he pulled it off brilliantly, saying, “I understand Solomon Dean Lipton was not one to suffer fools gladly, so I had better keep my comments brief and sit down.”

The floor opened to a tremendous creative outpouring of poems and remembrances. An old college friend from the 1930s recounted how the two of them used to wrangle non-stop all night and day, roping in whoever else they could into the debate. “And remember, he was Jewish!” she said. Gail Kaplan put it all together, saying, “Dean was the real thing in a world that too often isn’t. What you saw was what you got, like it or not. And I did. I liked his growling attitude toward life. I suspect it’s what kept him alive, kept him busy fighting a world that had been most unkind to him.”

One of Dean’s daughters got up and spoke to her dead father, pleading, “Please, Daddy. Please accept Jesus Christ into your heart so we can all be together in the afterlife.” There was awkward silence while everyone imagined Dean’s grumpy response, most likely his signature, “Oh great.” I felt sorry that her Mormon beliefs were making her loss feel even bigger at such a tender time.

Leonard compared Dean to a ship: “Not one of your sleek cabin cruisers but some gaunt ragged schooner that after braving the elements still scorns safe harbor and rests restlessly, ever ready to set sail again to unknown places.” I read a poem about Dean’s restless, wakeful, all-night walks, now finally ending in his last and deepest sleep… his body soon to rest in a Mormon cemetery out in the salt flats! Culture clash and all, this disparate commemoration added up to a most worthy send-off for inimitable Dean.

On the one-year anniversary of his death in 1993, writers gathered again to commemorate him with an even greater outpouring of poems and tales. Afterward, Leonard gathered the various elegies from far-flung Workshop writers, and I edited them into a chapbook, The Dean Lipton Memorial Anthology, published by Grow Like Weeds Press, founded in Dean’s honor.

Leonard ran the Writers Workshop at the State Building for two years after that. His style was very lowkey compared to Dean’s. He didn’t hold himself out as the expert or the last word but simply facilitated the readings and comments. When his partner Randy (aka Elinor Randall) moved back east to Vermont, he began spending summers there with her. It was time to turn the leadership of the workshop over to other reliable hands.

A young Afghan-American man had been coming to the Workshop since the mid-1980s and kept showing up through its ups and downs. I remember Tamim Ansary reading a wide range of works, starting with his translations of the poet Hafez, who I had never heard of until then, and his translations of his own father’s poetry from Farsi. He was hatching an intriguing novel, set in old-world Afghanistan before the Soviet invasion. What a blessing that Tamim stepped in to lead the San Francisco Writer’s Workshop, then moderated it masterfully for 22 years after.

This piece came out of my long participation in the San Francisco Writers Workshop and from interviews I did with several old-timers. It came equally from my lifelong friendship with Leonard Irving, Randy (Elinor Randall), and Daniel Borgstrom. We spent countless hours together around the hearth at their farmhouse, sharing Workshop memories. I can hardly tell anymore which of these words came from them and which came from me.

What a wonderful essay. Thank you for this piece of history. I wish I’d met Dean Lipton. I certainly heard about him a lot from the poet Janice King. He was well loved.

LikeLiked by 1 person